8 - 10 November 2019: Game Happens, Genova, Italy

10 - 12 October 2019: IndieCade Night Games, Santa Monica, USA

9 - 20 October 2019: Museum Tinguely, Basel, Switzerland

24 May - 7 June 2019: Foksal Gallery, Warsaw, Poland

28 September - 7 October 2018: Vienna Design Week, Austria

22 September 2018: Teatr Studio, Palace of Culture and Science, Warsaw, Poland

Everything is dead in cyberspace. None of the things we make with computers are alive. But some are three-dimensional, just like us. Some of them breathe, just like us. There are digital hearts that beat in digital chests. Eyes that stare at you, staring at them. It is hard to imagine that we cannot touch these beings, these virtual things, these digital objects.

They seem so real. Not like humans, or other objects that populate our tangible universe. Not like ideas or concepts or feelings or fantasies. Not even like distant planets and stars barely visible out there, somewhere. But they are here and they are real. They exist in some kind of reality. A reality that we can visit but can never really inhabit.

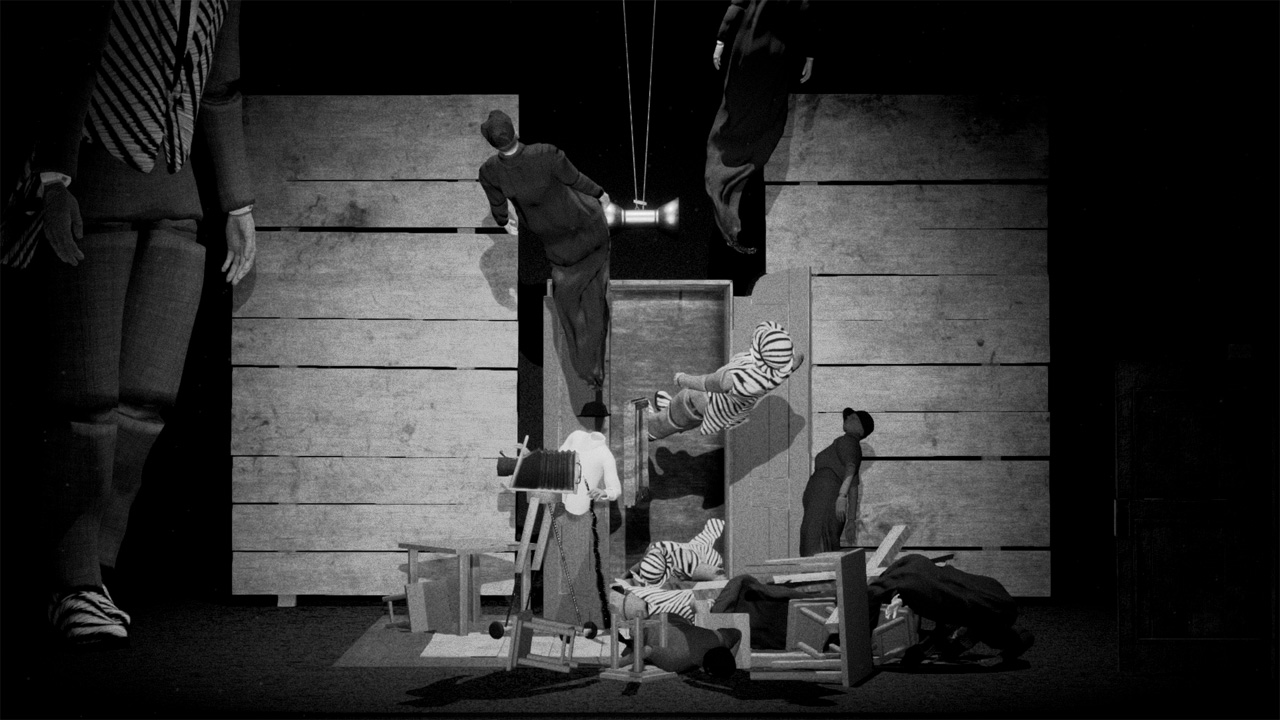

It is sentiments such as these that drew us to the theater of Tadeusz Kantor. On the Cricot2 stage, back in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s -right before the internet became accessible to the public- all objects were equal. A table, a device, an actor, a mannequin. They were all elements in the picture that the director, Tadeusz Kantor himself, always on stage, was creating. That creation seemed like an exploration, an exploration of memories, of images, of symbols, collective and individual. An experiment with putting things together to see what happens. To see what happens inside of him.

Cricoterie is inspired by Kantor's work. But it is not a recreation, nor a documentary, not even a tribute. We shamelessly plunder his art to create our own.

Cricoterie is a software program. To see it, you wear Virtual Reality goggles on your head, and to touch it you hold a Virtual Reality controller in each hand. Much like a theater performance, the experience takes place in the moment. There is no picture to hang on the wall, no song to play on your phone. Cricoterie only happens when the program is running on a computer. Cricoterie is live!

The user of Cricoterie finds themselves on a theater stage dominated by a large wardrobe. From that wardrobe, all sorts of objects emanate: stage props, some more alive than others. And you're the director.

You grab these objects and arrange them on stage, to see what will happen, inside of you. Some are static objects, like a chair or a wooden cross, others have movable parts, like a gallows or a door. Some are human figures. But much like in Kantor's theater, the nature of these figures is ambiguous. Are they alive or dead? Actors or mannequins? Or allegories, perhaps?

The human-shaped figures in Cricoterie are presented as life-size ball-jointed dolls. So in a sense, it is clear that they are objects. But they do have some autonomy. As dolls, however, they, much like the other objects, feel real, or real enough, or just not real enough. We are fascinated by this uncanniness.

The motions of these objects are driven by a physics simulation running in real time. This is a computer system that attempts to imitate the behavior of objects in nature. So they fall to the floor, collide with each other, are affected by wind and air, and so on. That system, however, is far from perfect. At times the simulation will cause extremely un-natural behavior. Cricoterie embraces these failings as integral to our uncanny world in cyberspace.

The stage props and actors appear not only in real time (no performance can ever be repeated) but also in real size. In Virtual Reality, we relate to the digital in a very physical way. As opposed to many other digitally mediated experiences, in VR, the body of the user is pivotal. The space we find ourselves in might be virtual, but our bodies still exist in the physical space that the illusion occupies. We approach the virtual objects in relation to our body. They are not just pictures on screens anymore as we enter their domain.

The area that is available for interaction covers only a portion of the virtual stage. This is due to technical limitations of the hardware (at the moment). But the user can change the scale of the world at will. By strategically make the world bigger or smaller (or themselves smaller or bigger) they can navigate the entire stage, by taking giant steps.

In reference to Kantor's Impossible Monuments, any object that the user is holding will retain its relative size when they return to the normal scale. As a result, a once life-size object can become unnaturally small or large. Nothing is impossible in cyberspace!

Cricoterie is a software program. And much like other software programs, apps, and internet services, it will continue to evolve. A first version of the program is launched in September of 2018. But updates will follow as we continue to expand the software. There is, however, no fixed plan, no predetermined design that we are working towards. Through interaction with the program and observation of and communication with its users, we decide which steps to take next. This organic way of working suits this project perfectly.

The Cricoterie program is available for free download. But since it requires a very powerful computer and dedicated hardware accessories, the optimal way to experience Cricoterie for most will probably be in physical installations that we hope to present many times in many places (like theater performances). Part of this installation is a projection of the stage area for onlookers to see what's going on in that virtual space.

Cricoterie is a creation of Auriea Harvey & Michaël Samyn. The couple met online when it meant something (in 1999), designed websites and created net.art as Entropy8Zuper! followed by more than a decade of independent videogame development as Tale of Tales. A few years ago they abandoned games to explore the artistic potential of computer technology further, under the banner Song of Songs. The couple lives and works in Ghent, Belgium.

The music in Cricoterie was composed by Gerry De Mol.

Cricoterie is a coproduction with the Adam Mickiewicz Institute and the Tadeusz Kantor Foundation. The production is supported by the Flanders Audiovisual Fund.

Further reading:

On errors and objects